Women Empowerment: high hopes and a disappointing reality What Prevents the...

Hate speech against women must come to End!

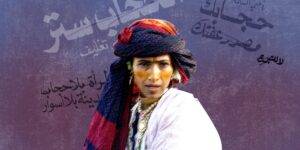

Do Sanaa’s walls hate women?

This Op-ed has been published on Daraj platform.

“I was browsing social media when I saw for the first-time a graffito on the walls of the city of Sanaa bearing expressions inciting hatred against women. I did not imagine that the streets of Sanaa would carry all these phrases targeting women. Today, I am not even able to remember the drawings that preceded those writings. All I remember is that they promoted peace and coexistence,” says Samar (pseudonym – 32 years old).

Yemeni women’s feeling that they are unwanted citizens has increased recently in public places and on the streets of the cities in which they live. A wave of public incitement targets women whose presence has begun to provoke a society afflicted with a constant and unjustified state of anger.

This incitement takes multiple forms, such as imposing strict requirements on dress code, determining “appropriate professions” for women, and restricting their freedom of travel and movement. The matter reached the point of describing women as a “source of strife” and the cause for “the delay in victory” in written, visual and audio speeches, the spread of which increases day after day under the slogan of “confronting the soft war” sometimes or “fighting immorality” at other times.

In Sanaa, at various times during the past two years, graffiti promoting peace and coexistence were omitted, and were replaced with expressions targeting women’s dress, freedom and personal life, and calling for male guardianship over them. Banners were also posted in public places, cafes, and parks expressing the same messages. Some of the banners bore the footer of official authorities, which may be understood as an official authoritarian speech in progress.

Samed Al-Sami a 30-years-old artist who used to participate in painting graffiti calling for peace in Sana’a, said: “By passage of time, Ansar Allah armed group (the Houthis) is further undermining the public sphere in a systematic and frightening manner. It has even reached the point of obliterating graffiti that oppose the war, replacing them with expressions that impose guardianship over women and target them as part of the soft war and a reason for delaying the victory. Such expressions on the walls that are ugly in look and reactionary in content. What will the future of the country be like with this violent, repressive approach?”

This adoption of the rhetoric of violence by authorities that have control over society is considered a dangerous turning point in the Yemeni context, in which women have not achieved their full rights, even in times of peace. Women have been oppressed for many decades, and responsibilities have been placed on them that appear to be to protect them, but inwardly are alienation and disqualification from them.

This discourse directed against women is based on the lack of development, the inefficiency of the state in providing its services to the countryside, and the high rates of ignorance and widespread illiteracy, even among males, which puts women before the choice of accepting hatred as a fait accompli, with the resultant complete fragility of their present and future.

The main concern about this matter is that this discourse targets an entire societal fabric, and is a flowing and continuous discourse, as if it were a regular path of an ideology that lacks logic at a minimum, an ideology that adopts distorted concepts of discrimination between members of society related to race, religion, political affiliation, and gender, and works to demonize women and doubts her “complete humanity”. It is also a constant incentive to make her an enemy of society.

This ideology mobilizes all its religious and customary potential to diminish women’s fundamental rights and even affect their presence in the public space.

There is no comprehensive definition of hate speech in international human rights law. Even the United Nations definition issued in 2019 is far from being an exhaustive definition and lacks a lot of clarification. However the definition, in its current form, it reasonably includes all authoritarian and religious practices and speech, heard and read, towards women and their role in Society, not to mention the specificity of the context in Yemen, through which this discourse can be transformed into violence applied directly to women, as it is sufficient to read in the United Nations report issued this year that “about 7.1 million women in Yemen need urgent access to services that prevent and treat Gender-based violence.”

It is clear that de facto authority in Yemen ignore agreements and treaties, whether we are talking about the CEDAW Convention of 1948, which Yemen signed, or even the Yemeni Constitution itself, which stipulates in Article (6) the importance of implementing United Nations charters. It is also noteworthy that Yemen tried, during the period of the National Dialogue Conference (2013-2014), to impose a 30 percent representation rate for women in government institutions and departments, but all of this was never sufficient to protect women.

Abolition of women quota

It is true that local laws in Yemen are unable to do justice to women, but the current armed conflict, which broke out in September 2014, has overturned all the outcomes of the national dialogue, reduced the level of sensitivity towards the situation of women, and abolished the quota right that was on the discussion table. In fact, it has reached the point of excessive symbolic violence hidden in social and ideological practices and acceptable behaviors and procedures, despite its extreme injustice to women’s rights, such as the use of the term “sisters for men” in the constitution.

The conflict played a fundamental role in stimulating this violence and legitimizing its behavior. For example, the absence of a fair and independent judiciary system marginalized the role of the Yemeni constitution guaranteeing the rights and protection of women. On the other hand, the absence and restriction of the freedom of independent media, whose job is to defend democracy, equality, and social peace, and the continuous attempts to eliminate the impartial and Conscious press, and to control all media outlets.

All of the above are elements that make the implementation of political, inflammatory and gender-discriminatory speeches come together without oversight or accountability, and make Yemen a fertile environment for cultivating hatred and fueling violence against women.

The parties to the conflict were not satisfied with this crude and intentional interference in the social fabric, but also fueled hate speech against women in professional, educational, and even judicial institutions, as they urged the reduction of the role of women in public life and criminalized their presence in it. It is frustrating to see how this intimidating behavior limited all women’s attempts to live their lives normally, and exposed their dignity to degradation, because the function of hate speech, within an environment that allows its application, intensifies in causing harm and stripping women of their rights or excluding them under threat, and inciting society’s hatred for everything related to them and their roles.

Friday sermon…a platform for misogyny

“I had to cover my face with a niqab, because the security personnel standing in front of the university entrance gate harassed me every day with insulting and bad words, saying that I was disrespectful and my father did not raise me well. This is because I used to wear colorful head coverings and Abayas. I don’t like the niqab at all because it bothers me and obscures my personality. I wear it against my will. I wish there was another way to stop the soldier’s bad behavior, because I was subjected to a lot of insults and looks of dissatisfaction, which is almost a common behavior adopted by anyone at the university who has authority,” says Rahma (pseudonym, 21 years old).

In Yemen today, the circle of hate speech has expanded, and harassment has moved from institutions to the streets and mosques, as Friday preachers have begun to talk about women and the way they dress and the importance of men’s guardianship over them, monitoring their phones and taking a look at them before leaving the house to ensure their commitment to the dress code that makes the intolerant society complacent to some extent.

The Friday sermon also reinforces the idea that war is linked to the presence of women as a sin, so she is stigmatized as being behind the so-called “soft war” or that her behavior and behaviors are a main reason for “postponing victory over the enemies.” Males, teenage boys, and girls constantly hearing such incitement which builds within them a growing grudge against women, which harms family structure and solidarity. Over time, the gap created between women and their families can be seen, increasing domestic violence and placing additional challenges and restrictions on women’s and girls’ involvement in social and economic life and educational institutions.

Maha (pseudonym – 34 years old) says, “I feel that the Friday sermon in the mosque targets me and all the women of the neighborhood. I have become an enemy to the majority of the neighborhood’s youth, even when they do not know who I am, but they know the mosque preacher who constantly describes women as part of a soft war in his sermon.”

As Yemenis’ access to social media increases, and the de facto authorities attempt to legitimize hate speech and violence against women, these means impose themselves as new and effective tools for disdaining women and degrading their status in society. These platforms witnessed slander and insult campaigns, and were even used for defamation, threats, and blackmailing, and one of them reached the point of attempting suicide on a live video, by shooting herself.

Sixteen days of each year are allocated for activism against gender-based violence, starting on November 25th. However, with the increasing forms of violence against Yemeni women, the conflict remains long. We mention here that at the beginning of November, a Yemeni woman was killed by a sniper while she was on her family’s farm in Al-Dhalea, south of Yemen, it was as if there was no safe place for a woman, not even her family’s land.

Our Latest Publications

Universal periodic review

Universal periodic review Submission Date : October 24, 2023 Fourth cycle,...